The Hidden Arithmetic of Meaning

A brief cultural history of gematria, numerology, and number in sacred architecture

HUMAN ORIGINS?SPIRITUAL AWARENESS

Nigel John Farmer

10/20/20254 min read

From the ancient Near East to today’s digital subcultures, people have turned to numbers to read the world more deeply, to reveal patterns, and to name destiny. In Jewish contexts this practice is called gematria, the mapping of letters to numbers to derive significance from names and verses. In the Greek world a related art flourished under the name isopsephy. Beyond these, numerology has been the wider umbrella under which civilisations have treated numbers as bearers of qualitative meaning as well as quantity.

The story often begins with alphabets that double as numerals. Hebrew and Greek scripts assign values to letters, which allows names, titles and phrases to be summed, compared and cross‑referenced. In late Hellenistic and rabbinic contexts gematria emerged as a recognised interpretive tool, one among many methods used to link scripture with scripture through shared values. Kabbalistic literature later systematised these correspondences, treating the fabric of language itself as numerically resonant. Greek isopsephy, which used Milesian numerals, functioned similarly, and in Christian late antiquity it sometimes shaded into mystical readings that paralleled Jewish practices, showing a shared cultural fascination with number and meaning.

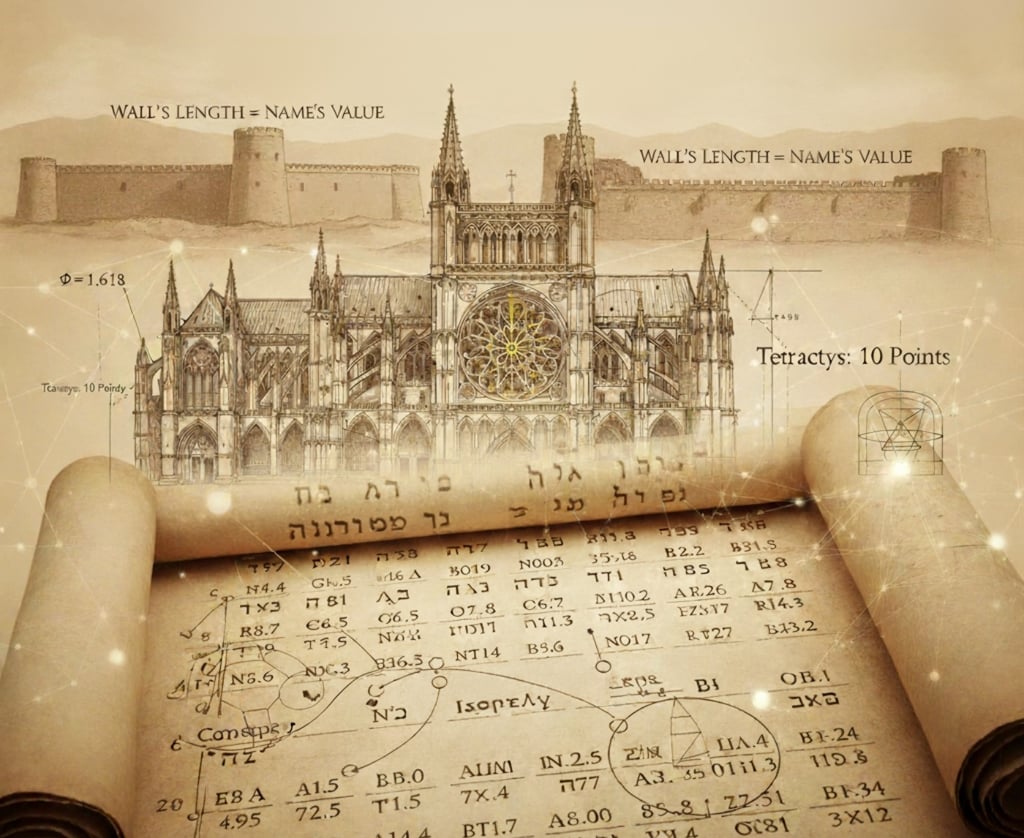

Ancient rulers also understood the theatre of numbers. A striking early example is Sargon II of Assyria, who reportedly specified the length of city walls to equal the numerical value of his royal name. This was more than arithmetic. It was a statement that kingship, city and cosmos were bound by the same harmonies, an early demonstration of numerology’s political power as a language of legitimacy and control. In later centuries, number symbolism threaded through courts and schools. Arabic scholars worked with abjad values, weaving letter‑number systems into sciences and esoteric traditions. In Europe, from scholastic classrooms to humanist studies, the notion that numbers possess qualities persisted, informing readings of scripture, nature and the arts.

The intellectual roots most cited in the West run to Pythagoras and his followers. For them, numbers were not merely a tool but the essence of reality. Cosmology, music and ethics were encoded in proportion and harmony, epitomised by the tetractys, a triangular figure of ten points revered as a symbol of order. These ideas influenced Plato and flowed into Neoplatonism, Christian mysticism and later Renaissance thought. They helped entrench a conviction that to know numbers was to know the hidden grammar of the world, an assumption that nourished both numerology and the mathematical sciences that would, paradoxically, later distance themselves from qualitative symbolism.

In Jewish tradition, gematria entered the exegetical toolkit alongside allegory, legal reasoning and other methods. Commentators drew connections between names and verses that shared numeric values, finding ethical prompts and theological insights in such links. While modern scholars caution against over‑reading coincidences, the practice is well attested and historically bounded by communal norms about how far one extends speculative conclusions. It is both playful and reverent, a hermeneutic that treats language as layered and generative, where meaning is not exhausted by plain sense but invites discovery.

Sacred architecture provides a different but related theatre for numbers. Medieval cathedral builders drew on symbolic geometry to align structure with metaphysics. Circles evoked eternity, squares the created order, triangles the Trinity. Proportional canons guided elevations and bays, animating stone with intelligible harmony. The so‑called divine proportion, later named the golden ratio, became a touchstone for designers seeking an embodied sense of balance. While historians debate the exactness of claims in each building, it is clear that sacred geometry served as a shared language, uniting craft, theology and mathematics in places like Chartres and other Gothic masterpieces.

Across cultures, letter‑number systems proliferated. Hebrew gematria, Greek isopsephy and Arabic abjad reveal a family resemblance. Each assigns values to letters, enabling ciphers, chronograms and commemorations. Inscriptions could encode dates or names. Texts could hide and reveal associations for initiates. The persistence of these systems speaks to a human desire to bind word and world through measure, to find that the shapes of writing are not arbitrary but resonant in the structure of things.

Modernity did not end this fascination. Encyclopaedias and surveys continue to track number symbolism’s influence across religions, literature and the arts. Educators introduce sacred geometry as a historical lens on design, while contemporary creators adapt numeric methods to plot structures, character naming and album sequencing. At the same time, critical scholarship urges caution: not every pleasing pattern is proof. The most fruitful stance treats gematria and numerology as disciplined arts within their traditions, open to inspiration but tempered by context, sources and method.

A brief glossary may help orient readers. Gematria refers to the Hebrew practice of deriving meanings through the numerical values of letters. Isopsephy names the Greek analogue. Sacred geometry gathers the symbolic use of shapes and proportions in design, especially in religious architecture. Each term points to a different facet of a shared conviction that number, language and form interpenetrate, and that by attending to their correspondences we might glimpse an order that is both intelligible and meaningful.

For those wishing to explore further, two pathways suggest themselves. One is historical narrative, following the arc from Sargon’s numerically keyed walls through Pythagorean philosophy to the vaults of Chartres, showing how leaders, schools and builders used numbers to imprint significance on matter. The other is practical demonstration, offering worked examples of classic Hebrew ciphers or Greek isopsephy, presented with appropriate caution about confirmation bias and framed within the interpretive norms of each tradition. Either path, or both in tandem, can invite readers into a conversation as old as writing itself and as current as today’s creative studios.

Nigel John Farmer

© 2023~2024~2025~2026 MeditatingAstronaut.com - All Rights Reserved Worldwide

website by Meditating Astronaut Publishing